Performance

I define performance as applying one’s insights and directed actions according to their talent in a given context. The context is determined by the challenges that stand between the current situation and the shared direction. The actor is therein responsible for applying his talents to best use, and no longer for the explicit result of those actions like in an output driven economy. It merely requires people who understand their responsibility as a contributor to the common goal. It is a sort of ‘contract social‘ (*) in which employer and employee engage when joining in an organisation. When accountabilities are being managed back to intrinsically driven responsibilities we need to reassess the traditional way of appraisal and performance management.

When we have established an organisation where the strategic direction and values are clearly communicated and shared, we no longer have to lay emphasis on the concrete output of its community. As outlined before, the desired output is a logical consequence of a healthy organisation where the crucial substance has been satisfied (a diverse community of intrinsically motivated people sharing the same values and direction). As a result the generated value (for both stakeholder and shareholder) increases and is expressed in the output in products and/or services. Performance management becomes climate management. The true challenge therefore is to manage the managers. It is the people manager community that is the catalyst for creating and maintaining a climate where the ‘specialists’ (who ultimately are those who add concrete value to the product) can give their meaning to the organisation

In short: the goal is to facilitate a climate in which the employees can operate in a meaningful way.

People do not come to work to complete a task, but they come to work to join a community that has shared values and direction. In their daily work they add value to the organisation by applying their talents in the strategic direction of the organisation. It is the people manager his responsibility (and inherently his talent) to facilitate his team in ‘giving meaning’. People managers are not teachers, neither are they quality controllers or need they to check on adherence. People managers are first and foremost mentors.

Mentors facilitate, give context (direction), advise and support. They do not pull or squeeze like they would in input/output driven organisations. This calls on an exploration of how to measure performance and reward fairly for individual contribution to the shared goals.

Let’s grow trees! We plant, water, feed and allow for some sun light. Its apples will make our effort tangible enough to justify our effort (and salary), but the business we are in is growing trees, not squeezing out the apples.

Performance management

When accountabilities are being managed back to intrinsically driven responsibilities we need to reassess the traditional way of appraisal and performance management.

When we have established an organisation where the strategic direction and values are shared, we no longer have lay emphasis on the concrete output of its community. As outlined before, the desired output is a logical consequence of a healthy organisation where the crucial substance has been satisfied (a diverse community of intrinsically motivated people sharing the same values and direction). Performance management becomes climate management.

The bell curve

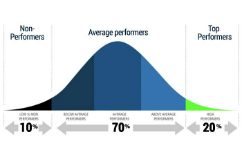

In large organisations the distribution of performance typically follows a so called bell curve or ‘normal distribution’. A minority underperforms and a minority exceeds in performance, leaving the majority delivering as expected. This is a likely outcome when two criteria are met:

- the number of people is large enough (statistical relevance)

- the performance of agents is measured relative to each other

The bell curve can emerge in two different ways.

- It can be found de facto after measuring a given distribution or

- it can be created by means of setting a rule that the distribution shall adhere to.

In the domain of performance appraisal this is a crucial difference. To pinpoint this difference and the consequences of applying one or the other we need to ask ourselves once more what we are trying to achieve by performance management. Is it to merely measure and compare individual performance to the performance of the wider population (ranking), or do we want to inspire attrition and recruitment by means of the existing distribution (raising the bar)?

I think it is fair to say that commercial organisations aspire to have the best workforce available to them and that they are willing to replace underperformers with talented candidates from the job pool. Appraisal is therefore not a mere label, but a strong statement about employee’s’ position and momentum in the organisation. It is reasonable for an organisation to ask appropriate performance in exchange for the salary it pays. Exceeding performance needs to be recognised and rewarded, while underperformance needs to managed differently.

Please allow me to focus on underperformance for now. Underperformance must be dealt with by either coaching (exposing individual skills in the direction of the organization’s strategy) or termination of the existing relationship and preferably ‘land’ the individual in a more appropriate setting, be it inside the organisation or elsewhere.

Key is how to define underperformance. If the underperformance is objectively assessed by the supervising manager we allow ourselves to evaluate the accumulated assessment distribution (expressed in ratings) with the bell curve. If, on the other hand, the bell curve is the predefined distribution that will be applied to the assessments (forced ranking), then the term applies to relative performance. In other words, an individual’s rating is subject to that of the population’s average.

Post appraisal evaluation

|

Pre appraisal ‘forced’ ranking

|

The bell curve is an analytical ‘tool’ to evaluate a given distribution. It is therefore not a goal that performance rating should adhere to. This is an important difference. Where the former evaluates the distribution, the latter determines the people’s relative performance rating. If we would predetermine that the ultimate performance distribution shall adhere to a normal bell curve, then the underperformers and role models are defined as a percentage of the community, independent of their actual behavior in the organisation. This is clearly not right.

There are a number of factors to be considered when choosing an appropriate approach even after having established that the organisation aims to replace the underperformers by new talent from the job pool:

- does the job pool deliver high(er) potential candidates that can bring fresh ideas to the organisation and compensate for the lack of experience and routine?

- Does the method impact morale of the existing workforce and does it attract highly motivated people from outside?

- Is the method chosen as a temporary ‘hygiene’ measure or is it a routine policy?

The core of the debate on forced ranking is not focused on the ranking as much as it is focused on its ‘forced’ nature. As illustrated, any wide population is likely to display a bell curve. Discontent arises around how this curve is established. Individuals in a forced ranking system, especially those labelled as underperformers, feel that their assessment is not based on their achievements, but simply as a sacrifice to the methodology.

In my opinion the bell curve is an analytical ‘tool’ to evaluate a given distribution. It is therefore not a goal that performance rating should adhere to. This is an important difference. Where the former evaluates the distribution, the latter determines the people’s relative performance rating. If we would predetermine that the ultimate performance distribution shall adhere to a normal bell curve, then the underperformers and role models are defined as a percentage of the community, independent of their actual behavior in the organisation. This is clearly not right.

Consider this:

In a particular year (T1) the organisation performs at the norm, leading to a normal distribution expressed in a even bell curve. In the next year (T2) the overall performance of the organisation as a whole gets better as a result of better performing people. Clearly the curve would shift to the right.

| even distribution in T1 | increased performance in T2 |

As a result of a better performing organisation there would relatively less underperforming people and more exceeding performers or even role models in a fair appraisal. As a result of a better performing community the curve responds accordingly.

If we would use the curve as a goal instead of an evaluation the curve would remain static. People who would have contributed to the organization’s results (equally as they have in the aforementioned example) would be rated less due to a statistical measure.

Of course there is a challenge that needs to be managed. In complex (matrix) organisations the performance rating is delegated according to the principles of subsidiarity, meaning that ultimately ratings are given in a dialogue between a manager and a member of his team (i.e. by the most decentralized competent member of the organisation). Because the effect of decentralization, managers might be asked to rate clusters of people that are too small for the statistical relevance of the bell curve. As a result ratings might be skewed by managers that do not recognize both under- and exceeding performance relative to the bigger performance of the organisation. This is why the people manager community needs a calibration.

further reading:

- analysis of the method of stack ranking (Stephen Gall)

- curves and stack ranking are not evil (Kevin Schofield)

- forced ranking: making performance management work (Dick Grote, Harvard Business School)

Calibration

In order to assess people fairly people managers need clear direction of what the different ratings entail. An exceeding performance in one team should be comparable to a similar performance in another team. Therefore people managers need to calibrate their views on what is the norm. It is important to note that it is the rating that is calibrated relative to the other measure, not an individual’s performance relative to his or her colleagues. If we would turn these two things around we would gravitate to a predefined (even) bell curve. It is important to keep in mind that the goal of calibration is to express the performance in objective terms, and not to rate relatively to a predefined distribution.

It is still common practice in many organisations to adhere to an ‘even’ or forced bell curve, despite the company’s performance. This has an unwanted effect on reward and recognition of the organised community. Both good and bad performance on a company level is not reflected in the rewards given. Especially when relative underperformance ultimately leads to ending the relationship between employer and employee. This is a Darwinist approach known as rank-and-yank or the vitality curve. It comes down to the cutting-off of a predefined percentage of the workforce for their (perceived) underperformance. These employees will have to be recruited on the market at an unknown cost given the logical requirement to recruit better staff to replenish the community.

Unwanted side effects are the politicization of the organisation. Especially in output driven organisations. Emerging fear of nepotism or even retribution on personal grounds (backstabbing). Even the perception of such a dynamic can undermine morale and motivation. People under stress of being ranked (or even yanked) will avoid taking risk or sign up to ambitious goals. Better safe then sorry.